Queer affordances layered within dating and hook-up apps

- Dani Penaloza

- Mar 25, 2020

- 10 min read

Updated: Aug 19, 2022

I have never used dating or hook-up apps in my life, and having been with my girlfriend for over five years now, I, personally, have no need to. Based on what others are telling me, I apparently dodged a bullet.

Despite not being on these apps or websites myself, I see and hear the frustrations from those using them nearly everywhere. I listen to my friends' first-hand experiences, see it from strangers' posts on my social media feeds, and even read about it in class readings.

It is no mystery that the digital space designed for seeking love and/or sex is often turbulent and challenging to navigate, but especially for queer folks.

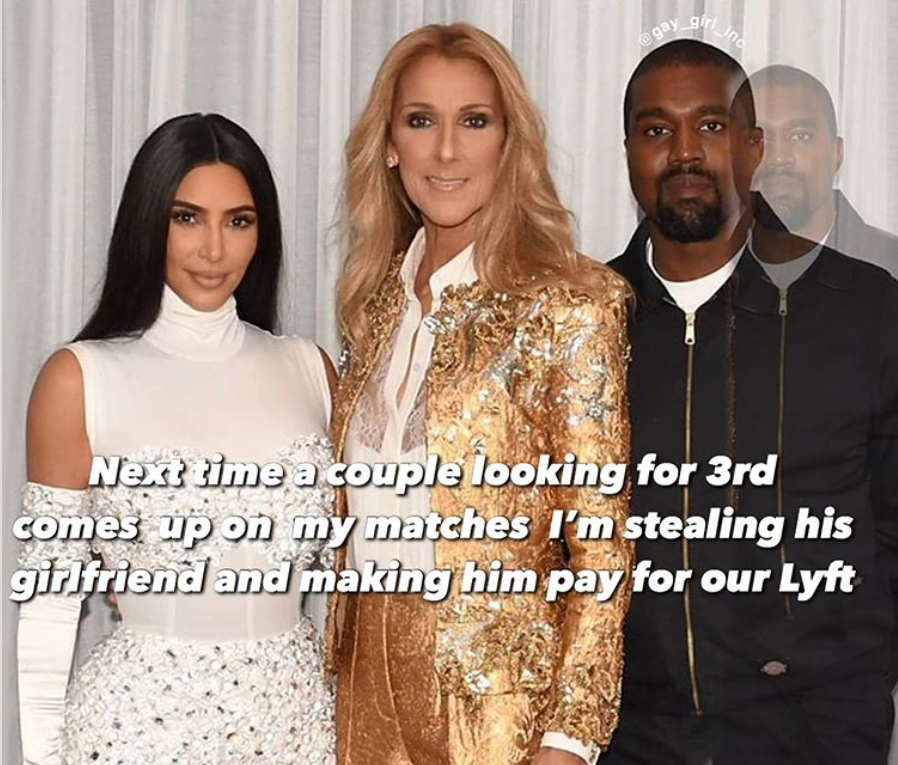

@gay_girl_inc on Instagram (left)

@lesbian.memezz on Instagram (below)

In this blog post, I will be employing Light et al.'s (2018) 'walkthrough method' to analyze the features and affordances encoded within the dating and hook-up apps Tinder and Lex that lend themselves to the queer community.

The question being explored is: How does an app designed for queer people offer more affordances to the community than an app designed for everybody?

But first, some key terms and previous works that are vital to answering this question.

Light et al.'s (2018) walkthrough method, which will be used to explore the two apps, involves establishing an app's intended use by looking at it's vision, its operating model, and it's governance. From there, registration and entry, everyday use of the app will be observed to analyze 'embedded cultural meanings and implied ideal users and uses.' (p.881). For the purpose of this exploration, discontinuation of use in the walk-through method will not be analyzed.

Adrienne Shaw's (2017) model of 'encoding and decoding' (Hall, 1973) technological affordances will be used to analyze the messages encoded or woven into the interface by designers, and what messages are being decoded or received by the users on how to use and navigate the apps.

Affordances here are defined as interactions between the world and it's actors, whether human or animal.

While Stuart Hall's initial model of encoding and decoding was used to explore media producers and audiences (1973), Shaw's model looks at designers of technology platforms, like apps, and users of them and how power differentials affect that relationship.

Shaw's model builds off Gibson's and Norman's concepts of affordances.

Gibson's concept of affordances (1979) centers around nature and the natural environment, where there is one true and correct way to interact with objects based on the object itself. Experiences of the subject interacting with the object are null, as well as personal knowledge, culture, and perception.

Norman's theory on affordances (1988 (revised 2015)) centers around the construction and human-made design of objects, that are up for creative interpretation of the subject interacting with them. If somebody is able to use that object in a certain way, that object lends that affordance. Personal experience and knowledge, and cultural influence do affect the subject's perception of the object's possible affordances.

The three types of affordances explained by Shaw (2017) will be looked at. Perceptible affordances are when an interface or platform looks like it should be able to do something and it is able to do that thing (Shaw, 2017). Hidden affordances are when a feature or use is not apparent to users, but the platform is capable of doing that function (Shaw, 2017). And finally, false affordances are when a platform appears to offer a feature or use, but it doesn't have the capacity to do so.

Ferdinand de Saussure's signifier/signified theory (1916) will be employed to analyze the semiotic features of the apps, including buttons, colours, fonts, symbols, and icons.

A sign is comprised of a signifier and a signified (1916), where the signifier is the stand-in for a meaning (like the word 'cool'), and the signified is the meaning or concept itself. A sign can have several meanings, or signifieds, which leads to the distinction between denotative and connotative meanings (Saussure, 1916).

Carrying the example of the word (i.e. sign) 'cool' forward, the denotative meaning is the dominant, dictionary definition of the word (see picture below). The connotative meaning is context-dependent, which means that the situation in which the word was said or read would hint at how it was meant to be interpreted. If said from one student to another, discussing their final exam being all multiple choice, 'cool' in this sense would clearly mean, or stand in for, 'great' or 'excellent.'

Denotative meaning of 'cool', Merriam Webster

Now, back to the apps.

As explained by Light et al. (2018), determining an app's "environment of expected use" (p.889) can be done by looking at their vision, operating model, and governance.

Let's look at Tinder's and Lex's vision.

Vision, in this sense, is the apps' "...purpose, target user base and scenarios of use ..." (Light et al., 2018, p. 889).

Tinder is clearly a dating/ hook-up app, but interestingly, it's tagline is "Match, Chat & Meet New Friends" on the Apple app store. Framing this app as a place to meet new "friends" may take the moral shame out of online dating and hooking up. This may indicate that the designers of the marketing for this app feel that these activities need to be disguised as something else.

"If you're here to meet new people, expand your social network, meet locals when you're travelling, or just live in the now, you've come to the right place."

Tinder is meant to be used anywhere and everywhere, according to their vision, including on vacations.

Further into the app's description it finally mentions dating, and then rejection.

Part of their vision includes shielding its users from the stress of potential rejection.

This anti-rejection claim seems to fall under the category of false affordances, as it is completely possible to get rejected later in the chat function of the app.

But, hey, at least you won't witness getting rejected right out of the gate with your profile getting a swipe left!

As for Lex's vision, here's what their 'about' page on the app had to say.

"Lex is a lo-fi, text-based dating & social app for lesbian, bisexual, asexual, & queer people. For womxn & trans, genderqueer, intersex, two spirit, & non-binary people. For people of marginalized genders, inspired by old school newspaper personal ads."

Their vision acknowledges that the intent of this app is to date, but also to socialize among other queer people.

Notably, this app doesn't allow photos in profiles. However, it does offer a hidden affordance of connecting a profile to Instagram, which is only viewable if you click the person's profile on their ad.

Importantly, this leads into who the target audience for these apps is.

For Lex, it is stated in their vision--all queer people, minus cis men, whether they're queer or not.

In a study on gendered usage of Tinder, Duncan and March (2019) found that men are more likely to use the platform for sexually coercive purposes.

Lex excluding cis men from this platform may lend a perceptible affordance of safety among a more-marginalized community.

Seeing as how this app is phone-based, it already caters to the technologically-savvy user, which may or may not be a young person. But because it started out as an Instagram account, and it is still relatively new, the target user would likely have found out about it through Instagram, through some other type of media, or through fellow-queer friend referral.

Lex's target user appears to be a phone-savvy queer person involved in the community enough to hear about the app, who wants something different with the no-pics-allowed-profile.

As for Tinder, the target audience is people of all identities and genders. There are no blatant exclusions, like in Lex, but it definitely markets towards young people.

All of Tinder's marketing on the Apple app store includes people in their 20s.

Tinder's target user appears to be a 20-something year old who is comfortable navigating on their phone and who appreciates filtering through potential matches in a visually-based way.

Featuring up to 9 pictures on a profile can be encoded as an emphasis on physical features in attraction, perhaps promoting the notion of judging a book by its cover.

An app's operating model includes its business strategy and ways of making income (Light et al., 2018).

Lex's beginnings started as a Kickstarter project back in 2018. It was also being funded by people submitting their ads to the original Instagram account, Personals, for a cost of $5-$10 (Lex, n.d).

The app is free to download, and there don't appear to be any in-app purchases. On their website, they say they are looking for investors. There are no job postings on their wesbite.

Tinder, on the other hand, has 42 jobs available which are posted on their website ("Jobs at Tinder", retrieved March. 25).

While their app is free to download, it includes in-app purchases like Tinder Gold. Subscribing to this service unlocks certain functions, like unlimited rewinds and likes, viewing who likes you, and turning off ads.

I think those subscription costs speak for themselves.

Tinder is much more of an empire than Lex, and even partners with Spotify.

In 2019, Tinder made $1.2 billion in revenue under the umbrella of Match Group, which owns Hinge, OkCupid, and Match.com (Carman, 2020).

Moving onto governance, this is how app use is regulated and governed by designers (Light et al., 2018).

This is usually reflected in the app's rules on conduct and who is allowed to use the app (Light et al., 2018).

Both Tinder and Lex are 18+ apps. Here are both of their rules that get displayed upon signing up, that you must agree to before proceeding.

Tinder's "house rules" are starkly different than those of Lex. Tinder focuses on not catfishing, treating others nicely, and maintaining safety.

Lex focuses on anti-oppression and discrimination in their rules--no transphobia, racism, fatphobia, ableism or hate speech of any kind.

The difference between the two seems to highlight the different communities that these apps serve--everybody versus the queer community (minus cis men).

As part of a community that is already marginalized, Lex attempts to protect its users from oppression within its platform, another queer affordance. Whereas, Tinder's rules seem more concerned about authenticity and kindness, as these other issues like transphobia, appear to not be on it's radar.

But let's get into actually using these apps now.

Following the walkthrough method (Light et al., 2018), I'll begin with the registration and sign up.

In order to sign up for Tinder, you must connect with Facebook or with your phone number. Lex is the same, but instead of the option of Facebook, it offers Instagram.

Both apps require your name, age, email, and location.

While Tinder requires you to pick your gender, among man, woman, and 'other' which includes a long list of identities, Lex simply requests your pronouns.

Tinder asks who you're interested in (men, women, or everyone), how you identify, and gives you the option of showing people of the same sexuality as yours, first, in your matches. It also requires you submit at least 1 picture to add to your profile, and identify how old you are.

Lex follows a less intrusive self-identification process because it assumes you are queer. It allows for you to disclose how you identify in your posted ads if you want to do so, and only requires pronouns on your profile as opposed to choosing from a list of identities. This is a queer affordance in itself, allowing you to avoid being plunked into a box if you prefer not to.

Next, the "everyday use" of these apps (Light et al., 2018).

Tinder allows you to:

- swipe through profiles that contain up to 9 pictures, and up to 500 characters bio.

- adjust your distance radius

- adjust your age range

- recommend profiles to a friend

- swipe left to "NOPE", right to "LIKE", and up to "SUPER LIKE"

- adjust notifications settings

Lex allows you to:

- scroll through text-based ads or missed connections

- write up to 3 'ads' in 30 days that will remain posted for 30 days

- adjust your distance radius

- adjust your age range

- search by key words

- adjust notifications settings

Here are some findings from exploring the two apps.

Despite identifying as "Gay", "Lesbian", and "Pansexual" on Tinder and selecting "Show me women", too many men were popping up in my deck of profiles.

How? I am unsure.

But this is nothing new, according to Ferris and Duguay (2020).

"By configuring settings to 'seeking women,' participants perceived they were entering a space conducive to finding WSW. However, men, couples, and heterosexual women permeated this space..." (p. 489).

Men magically popping up into a feed that was supposed to only show women, is not a queer affordance. And by offering a button to select that you only want to see women, and then showing men, is a false affordance.

As for Lex, because of it's text-based nature, there was a lot of queer lingo and terms being used that are very specific to the community. I can see how somebody who was unfamiliar could get overwhelmed with all the terms and identifiers.

Here are some terms that I wrote down during this process.

- moc lesbians - masc. of centre lesbians

- futch - femme butch

- gnc femme -gender non-conforming femme

- enby - non binary

Queer social media spaces, and in this case, queer dating apps, have long served as learning environments for those discovering their identities (Fox & Ralston, 2016).

Learning more about who makes up such a large, diverse community can help with self-acceptance and finding out more about yourself.

Lex serves not only as an app for connecting with others, but it also offers the important affordances of visibility, anonymity, and interactivity (Fox & Ralston, 2016) to part of the community struggling with their identity, as well as to those completely comfortable with their identity.

A breakdown of some signs.

Logos:

- reddish orange colour encoded as warmth and heat, which could be associated with sexiness

- flame encoded as fire, hot, again representing desire, passion.

- neon blue colour encoded as attention-grabbing, important

- 'lex' phonetically sounding close to 'sex' and also associated with the queer women club, The Lexington Club, which was known as the The Lex.

Conclusion

It, of course, makes sense that an app designed for queer people would offer more queer affordances, such as selective self-identification of sexuality and gender, asserting pronouns, and purposely excluding men from the space.

By choosing not to include pictures on profiles, Lex stands apart from most dating and hook-up apps in that it doesn't encourage hyper-focusing on looks, something enforced by the patriarchy and by heteronormative culture.

References:

Carman, A. (Feb. 4, 2020). Tinder made $1.2 billion last year off people who can't stop swiping. The Verge, retrieved from https://www.theverge.com/2020/2/4/21123057/tinder-1-billion-dollars-match-group-revenue-earnings.

Duncan, Z. & March, E. (2019). Using Tinder to start a fire: predicting antisocial use of Tinder with gender and the dark tetrad. Personality and Individual Differences, 145, 9-14.

Ferris, L. & Duguay, S. (2020). Tinder's lesbian digital imaginary: investigating (im)permeable boundaries of sexual identity on a popular dating app. New media & society, 22(3), 489-506.

Fox, J. & Ralston, R. (2016). Queer identity online: informal learning and teaching experiences of LGBTQ individuals on social media. Computers in Human Behaviour, 65, 635-642.

Gibson, J. (1979). "The theory of affordances." The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception. New York: Psychology Press.

Hall, S. (1973). Encoding and decoding in the television discourse.

"Jobs at Tinder." (n.d). Retrieved on March 25 from https://gotinder.eightfold.ai/careers

"Lex." (n.d). Retrieved from https://thisislex.app

Light, B., Burgess, J. & Duguay, S. (2018). The walkthrough method: an approach to the study of apps. New media and society, 20(3), 881-900.

Norman, D. (2013). The Design of Everyday Things, revised and expanded version. New York: Basic Books.

Saussure, F. (1916). Course in general linguistics.

Shaw, A. (2017). Encoding and decoding affordances: Stuart Hall and interactive media technologies. Media, Culture & Society, 39(4), 592-602.

.jpg)

Comments